SOLID

SOLID design principles are a set of guidelines that help developers create better-structured, more manageable code.

-

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP): Understanding how to ensure that each class has only one responsibility and how this helps in keeping the code maintainable.

-

Open/Closed Principle (OCP): Learning to design classes that are open for extension but closed for modification, allowing for easier addition of new features.

-

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP): Exploring how to design class hierarchies where derived classes can be used interchangeably with their base classes without breaking the system.

-

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP): Understanding how to keep interfaces small and focused, avoiding the problem of "fat interfaces" that force classes to implement unnecessary methods.

-

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): Learning to decouple high-level modules from low-level details by introducing abstractions, making the system flexible and easy to maintain.

The SOLID Principles

S - Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Single Responsibility Principle states that a class should have only one reason to change. In other words, a class should only do one thing or be responsible for one task. This makes the system simpler, as each class has a specific responsibility. If something needs to change, it will only affect that class.

O - Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

The Open/Closed Principle means that software entities (like classes or methods) should be open for extension but closed for modification. This allows developers to extend the functionality of existing classes without changing the class itself. The goal is to avoid making unnecessary changes to existing code, which can introduce new bugs.

L - Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle ensures that objects of a subclass should be able to replace objects of the superclass without affecting the correctness of the program. This means subclasses should not break the functionality defined in the parent class, ensuring consistent behavior across the system.

I - Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Interface Segregation Principle advises that clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use. Instead of having one large interface, break it down into smaller, more specific ones. This way, each class implements only the methods it needs, making the code cleaner and easier to work with.

D - Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle states that high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. This principle reduces tight coupling between modules, making the system more flexible and easier to modify. It helps create loosely coupled code by relying on abstractions rather than concrete implementations.

SRP - Cohesion and Coupling

What is Cohesion - High cohesion → Single Responsibility Principle

Cohesion refers to how closely related and focused the responsibilities of a class, module, or method are.

A highly cohesive class will have methods that work together to achieve a single purpose. On the other hand, low cohesion occurs when a class has unrelated responsibilities bundled together, which makes it harder to maintain and understand.

To follow the Single Responsibility Principle, your classes need high cohesion. Why? Because high cohesion means that a class focuses on a single responsibility or task, which is exactly what SRP demands.

- Low cohesion often results in a class with multiple unrelated responsibilities, violating the SRP.

- High cohesion ensures that each class or module is centered around one responsibility, making the code easier to maintain and extend.

By organizing your code to have high cohesion, you naturally follow the SRP, as each class or component will focus on a single, clearly defined responsibility.

What is Coupling? Low coupling → Dependency Inversion Principle

Coupling refers to how closely connected different modules, classes, or methods are to each other.

In software design, we aim for low coupling, meaning that classes and components should be as independent from each other as possible. High coupling, on the other hand, means that classes are tightly dependent on one another, making it harder to change or reuse parts of the system.

Reducing coupling makes it easier to follow the Single Responsibility Principle. Here’s why:

- High coupling often means that classes are doing too much, leading to multiple responsibilities, which violates SRP.

- Low coupling helps ensure that each class focuses on a single responsibility, making the code more modular, easier to maintain, and simpler to understand.

By splitting the responsibilities (like student management and database operations) into different classes, we maintain low coupling and follow SRP. This ensures that each part of the system is focused and independent, making future changes much easier.

Explaining Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

Let’s now break down these two important terms:

-

Closed for Modification means that once a class, function, or module is written and tested, it should not need to be changed in the future to accommodate new behavior. By keeping the core code unchanged, you ensure that the tested and stable parts of the system remain reliable. If every change required modifying the existing code, you could introduce new bugs or break the functionality that has already been proven to work.

-

Open for Extension means that you can add new functionality to the system without modifying the existing code. This is typically achieved through techniques like inheritance, interfaces, or polymorphism, which allow you to extend the behavior of the code by adding new components (like subclasses or new methods) rather than modifying what’s already in place. This keeps the system flexible and adaptable while preserving the integrity of the original code.

How OCP Is Related to SRP

Each SOLID principle is related to each other.

The Open/Closed Principle is closely connected to the Single Responsibility Principle. Here's how:

-

Decoupling in OCP: In OCP, we decouple functionality by separating the core code from extensions. This makes it easier to add new features without affecting the core.

-

Single Responsibility Focus: By decoupling and creating independent modules or classes for different functionalities, you’re naturally following the Single Responsibility Principle. Each class or module is responsible for one task, making it easier to manage and extend.

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) is an important concept in object-oriented design. It states:

"Objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of a subclass without affecting the correctness of the program."

This principle means that a subclass should behave in a way that it can substitute for its parent class without causing issues in the system. If a subclass breaks the behavior expected from the parent class, it violates LSP.

When to Break the Hierarchy

-

When Subclasses Can’t Implement Parent’s Behavior: If a subclass can’t fully follow the parent’s contract (e.g.,

ElectricCarrefueling), it’s time to rethink the hierarchy. -

When Subclasses Behave Too Differently: If subclasses have vastly different behaviors, a more general parent class may be needed to avoid forcing inappropriate methods on subclasses.

-

When Conditionals Increase: If you're adding too many conditionals in subclasses, it's a sign that the hierarchy isn’t flexible enough and needs refactoring.

Breaking the hierarchy is useful when you notice these patterns, helping you build more flexible and maintainable systems.

Using Composition to Follow Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

In the previous lesson, we explored how using inheritance can sometimes violate the Liskov Substitution Principle. Another way to follow LSP without falling into the pitfalls of inheritance is by using composition over inheritance. This method allows you to design systems that are more flexible and avoid situations where subclasses cannot properly fulfill the parent class's contract.

Example: Bird and Flying Behavior

Let’s use the example of birds. If we use inheritance, we might create a Bird class that defines general bird behaviors, like flying. However, some birds—like penguins—cannot fly.

Inheritance forces subclasses to implement or override behaviors they don’t need, which can lead to LSP violations.

Solution: Using Composition to Follow LSP

To avoid this issue, we can use composition. Instead of forcing birds to inherit flying behavior, we can create a separate Flyable interface and only assign flying abilities to birds that can actually fly.

Using composition over inheritance allows us to avoid violating the Liskov Substitution Principle. By separating specific behaviors like flying into an interface, we avoid forcing all bird subclasses to implement or override methods that don’t apply to them. This creates a more flexible, maintainable design that follows LSP and allows each class to behave according to its own characteristics.

Why is LSP Important?

- Prevents Fragile Code: LSP helps avoid situations where subclass behavior violates the expectations set by the parent class. This prevents fragile code where one small change in a subclass can break the system.

- Improves Flexibility: By designing classes that can be substituted without breaking the parent contract, you create flexible systems that allow for easy extension and maintenance.

- Ensures Correctness: When LSP is followed, the correctness of the program is maintained, as subclasses respect the rules and behaviors of their parent classes, ensuring reliable, predictable results.

- Promotes Code Reusability: LSP makes it easier to reuse base classes and create new subclasses without having to modify existing code, keeping your system scalable and reusable.

LSP is vital because it upholds the integrity of your class hierarchy, ensuring that extending functionality or creating new subclasses won’t disrupt the program’s existing behavior. It keeps your code clean, modular, and safe to evolve over time.

Interface Segregation Principle

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) is the fourth principle in the SOLID design principles. It states:

"Clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use."

This means that a class should only implement the methods it actually needs. Large, general-purpose interfaces can become problematic when they force implementing classes to include methods they don't require. Instead, it's better to create smaller, more focused interfaces.

By restructuring the code:

- Smaller, Focused Interfaces: Each interface now represents a specific task (printing, scanning, faxing, or stapling). This allows classes to implement only what they need, following the Interface Segregation Principle.

- More Flexible Design: Classes like

BasicPrinteronly need to implement thePrinterinterface, avoiding unnecessary methods. Meanwhile,AdvancedPrintercan implement multiple interfaces to support a range of functionalities. - Cleaner, Easier to Maintain Code: The code is easier to understand and maintain since each class focuses on the exact responsibilities it needs to fulfill.

Techniques to Identify ISP Violations

1. Low Cohesion

Low cohesion happens when a class tries to handle multiple unrelated tasks, making the class less focused and harder to maintain. Low cohesion often leads to ISP violations because the class implements more methods than necessary.

2. Fat Interface

A fat interface is one that contains too many methods, usually covering multiple unrelated functionalities. Fat interfaces force classes to depend on methods they don’t need, leading to bloated code and ISP violations.

3. Empty or Unsupported Methods

When classes implement an interface and include empty or unsupported methods, it’s a clear sign of an ISP violation. Classes should not be forced to implement methods they won’t use.

4. Classes with Too Many Responsibilities

When a class has too many responsibilities, it often implements multiple methods from a large interface. This indicates that the interface may need to be broken into smaller ones.

How ISP Relates to Other SOLID Principles

-

SRP: ISP supports SRP by keeping interfaces focused on a single responsibility, ensuring that classes implement only what they need.

-

OCP: ISP aligns with OCP by making it easy to extend systems with new interfaces without modifying existing ones.

-

LSP: ISP helps with LSP because classes implementing smaller interfaces respect their contract, making substitution safer and more predictable.

Dependency Inversion Principle

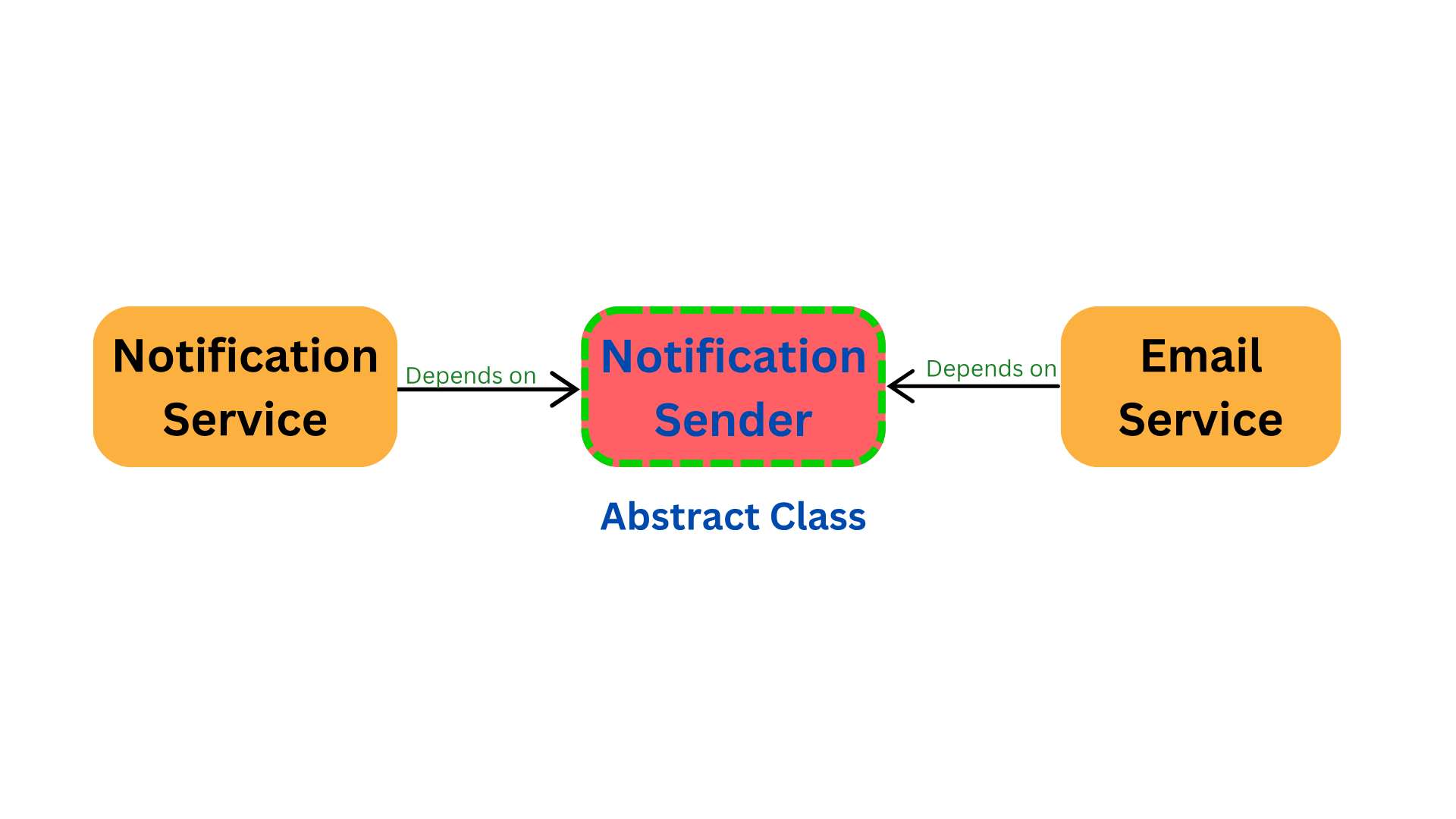

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) is the final principle in the SOLID design principles. It states:

"High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions."

"Abstractions should not depend on details; details should depend on abstractions."

These statements emphasize that software design should prioritize flexibility and decoupling by ensuring that high-level policies are not directly tied to low-level implementation details. Both high-level and low-level modules should rely on abstractions (e.g., interfaces or abstract classes) to establish a flexible relationship. This approach keeps the system modular and adaptable.

Key Concepts of DIP

- High-Level Modules: These are components that contain the core business logic of the application. They should dictate the flow of the application without being dependent on specific implementation details.

- Low-Level Modules: These modules handle specific, detailed tasks, such as database operations or network communication. They should not directly control the application's main flow.

- Abstractions: Interfaces or abstract classes that define general behaviors. High-level and low-level modules depend on these abstractions to communicate, keeping the system loosely coupled.

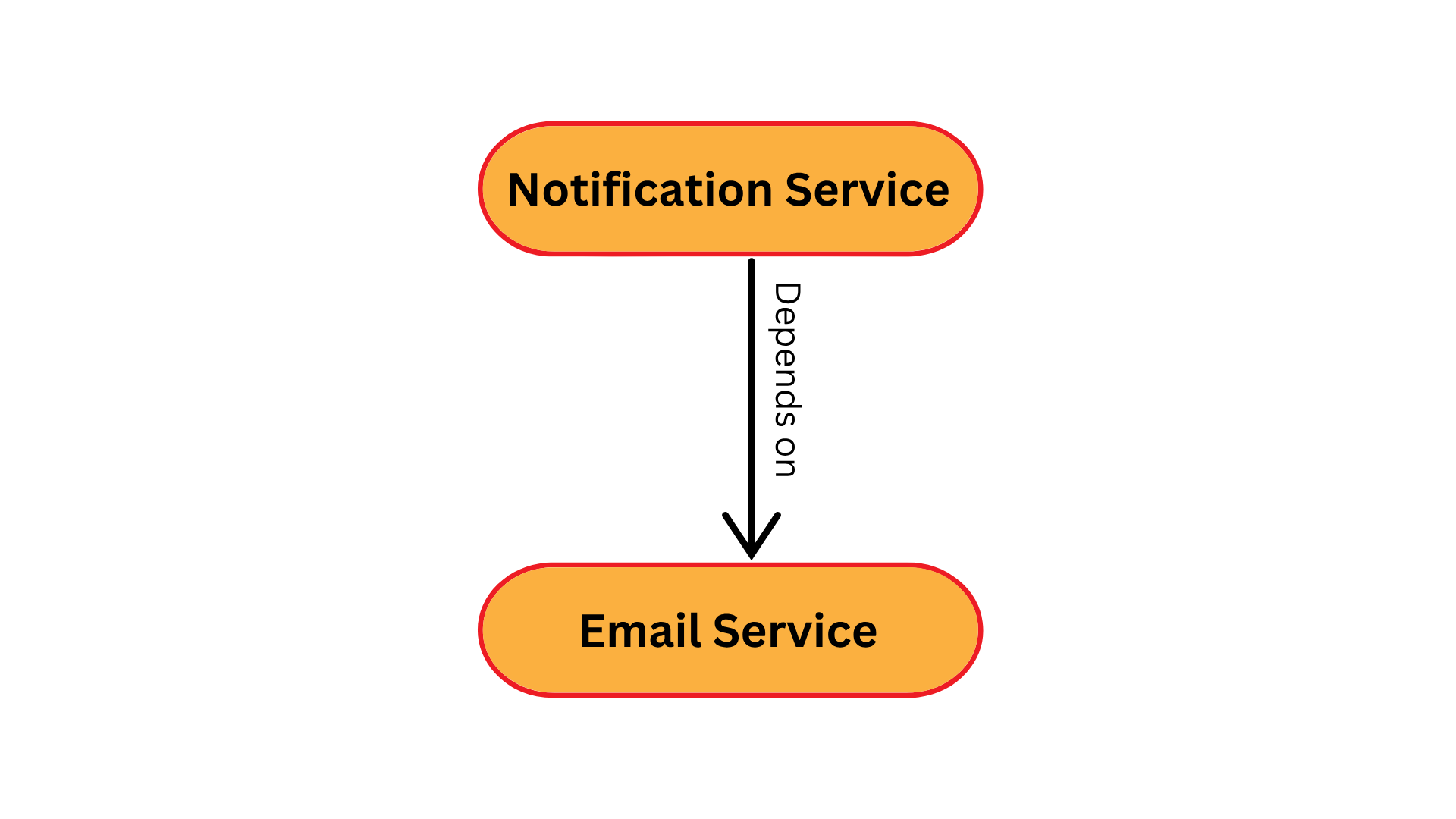

- Tight Coupling: The high-level module (

NotificationService) is directly tied to a specific low-level implementation (EmailService). Changes in the low-level module require changes in the high-level module. - Lack of Flexibility: Switching to another notification type (e.g., SMS or push notifications) is not possible without modifying the existing code.

using System;

// Abstraction for sending notifications

public interface NotificationSender

{

void send(string message);

}

// EmailService that implements NotificationSender

public class EmailService : NotificationSender

{

public void send(string message)

{

Console.WriteLine("Sending email: " + message);

}

}

// SMSService that implements NotificationSender

public class SMSService : NotificationSender

{

public void send(string message)

{

Console.WriteLine("Sending SMS: " + message);

}

}

// High-level module that depends on the NotificationSender interface

public class NotificationService

{

private NotificationSender notificationSender;

// Constructor takes a NotificationSender, allowing for flexibility

public NotificationService(NotificationSender notificationSender)

{

this.notificationSender = notificationSender;

}

public void send(string message)

{

notificationSender.send(message);

}

}

// Main class to test the refactored design

public class Solution

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Using EmailService as the NotificationSender

NotificationSender emailService = new EmailService();

NotificationService notificationService = new NotificationService(emailService);

notificationService.send("Hello via Email");

// Switching to SMSService without changing NotificationService

NotificationSender smsService = new SMSService();

notificationService = new NotificationService(smsService);

notificationService.send("Hello via SMS");

}

}

Dependency Injection

Dependency Injection (DI) is one of the most popular ways to apply DIP. It involves providing the dependencies (i.e., low-level modules) to a class from the outside rather than having the class create its own dependencies. This allows the high-level module to depend on abstractions, making the system more flexible.

Inversion of Control (IoC) Frameworks

IoC frameworks such as Spring in Java, or .NET Core in C#, use dependency injection to apply DIP at scale. These frameworks manage the lifecycle and dependencies of objects for you, allowing for loosely coupled architecture.

Applying the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) in real-world scenarios promotes flexibility, modularity, and maintainability in software design. Techniques such as dependency injection, service locators, IoC frameworks, and plugin architectures enable systems to follow DIP effectively, ensuring that high-level policies remain decoupled from low-level implementations.

Importance of DIP

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) plays a crucial role in creating flexible, maintainable, and decoupled software. By ensuring that high-level modules do not depend directly on low-level implementations, DIP allows for:

- Better Flexibility: The system can easily accommodate changes by swapping implementations without affecting the overall design.

- Improved Maintainability: Decoupled components make it easier to modify or extend features while minimizing the impact on existing code.

- Enhanced Testing: Mocking dependencies for testing becomes straightforward, enabling thorough and isolated unit testing.

How DIP Relates to Other SOLID Principles

-

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP): DIP supports SRP by decoupling classes and minimizing dependencies. This ensures that each class focuses on one responsibility, while the details are abstracted away.

-

Open/Closed Principle (OCP): DIP helps achieve OCP by making modules open for extension but closed for modification. High-level modules rely on abstractions, allowing for easy extension by introducing new implementations.

-

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP): DIP complements LSP by ensuring that subclasses or implementations adhere to a common interface, making substitutions safe and seamless.

-

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP): DIP encourages designing smaller, specific interfaces. High-level modules can then depend on minimal abstractions, avoiding fat interfaces and ensuring that each module only uses what it needs.