CAP

At its core, CAP theorem states that in a distributed system, you can only have two out of three of the following properties:

-

Consistency: All nodes see the same data at the same time. When a write is made to one node, all subsequent reads from any node will return that updated value.

-

Availability: Every request to a non-failing node receives a response, without the guarantee that it contains the most recent version of the data.

-

Partition Tolerance: The system continues to operate despite arbitrary message loss or failure of part of the system (i.e., network partitions between nodes).

In practice, since network partitions are unavoidable, this means choosing between consistency and availability. In any distributed system, partition tolerance is a must. Network failures will happen, and your system needs to handle them.

Choosing consistency means that all nodes in your system will see the same data at the same time. When a write occurs, all subsequent reads will return that value, regardless of which node they hit. However, during a network partition, some nodes may become unavailable to maintain this consistency guarantee.

On the other hand, opting for availability means that every request will receive a response, even during network partitions. The tradeoff is that different nodes may temporarily have different versions of the data, leading to inconsistency. The system will eventually reconcile these differences, but there's no guarantee about when this will happen.

In a system design interview, availablity should be your default choice. You only need strong consistency in systems where reading stale data is unacceptable.

Examples of systems that require strong consistency include:

- Inventory management systems, where stock levels need to be precisely tracked to avoid overselling products

- Booking systems for limited resources (airline seats, event tickets, hotel rooms) where you need to prevent double-booking

- Banking systems where the balance of an account must be consistent across all nodes to prevent fraud

The key characteristic of these systems is that any inconsistency, even temporary, could lead to significant business or technical problems.

Don't feel pressured to choose a single consistency model for your entire system. Different features often have different requirements. In an e-commerce system, product descriptions can be eventually consistent while inventory counts and order processing need strong consistency to prevent overselling.

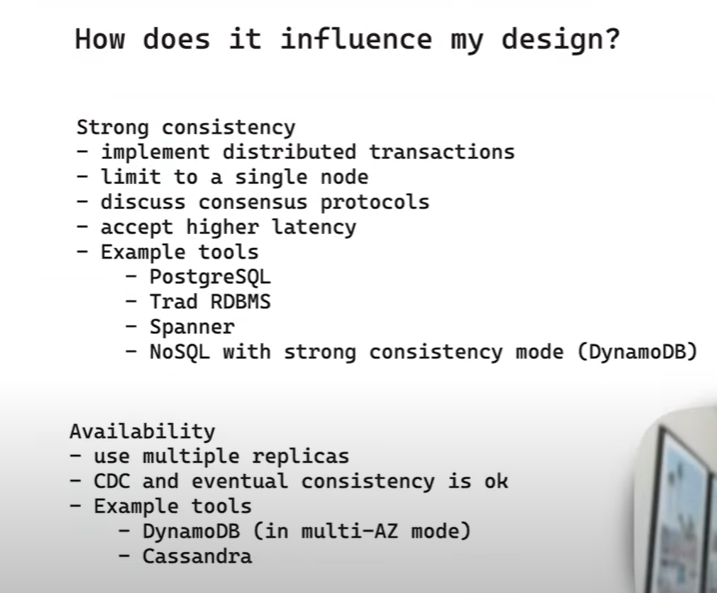

How does it influence my design?

When discussing non-functional requirements, CAP theorem should be your starting point. You need to ask the all important question: "Does this system need to prioritize consistency or availability?"

If you prioritize consistency, your design might include:

-

Distributed Transactions: Ensuring multiple data stores (like cache and database) remain in sync through two-phase commit protocols. This adds complexity but guarantees consistency across all nodes. This means users will likely experience higher latency as the system ensures data is consistent across all nodes.

-

Single-Node Solutions: Using a single database instance to avoid propagation issues entirely. While this limits scalability, it eliminates consistency challenges by having a single source of truth.

-

Technology Choices:

-

Traditional RDBMSs (PostgreSQL, MySQL)

-

Google Spanner

-

DynamoDB (in strong consistency mode)

-

On the other hand, if you prioritize availability, your design can include:

-

Multiple Replicas: Scaling to additional read replicas with asynchronous replication, allowing reads to be served from any replica even if it's slightly behind. This improves read performance and availability at the cost of potential staleness.

-

Change Data Capture (CDC): Using CDC to track changes in the primary database and propagate them asynchronously to replicas, caches, and other systems. This allows the primary system to remain available while updates flow through the system eventually.

-

Technology Choices:

Different Levels of Consistency

When discussing consistency in CAP theorem, people usually mean strong consistency - where all reads reflect the most recent write. However, understanding the spectrum of consistency models can help you make more nuanced design decisions:

Strong Consistency: All reads reflect the most recent write. This is the most expensive consistency model in terms of performance, but is necessary for systems that require absolute accuracy like bank account balances. This is what we have been discussing so far.

Causal Consistency: Related events appear in the same order to all users. This ensures logical ordering of dependent actions, such as ensuring comments on a post must appear after the post itself.

Read-your-own-writes Consistency: Users always see their own updates immediately, though other users might see older versions. This is commonly used in social media platforms where users expect to see their own profile updates right away.

Eventual Consistency: Updates will propagate eventually. The system will become consistent over time but may temporarily have inconsistencies. This is the most relaxed form of consistency and is often used in systems like DNS where temporary inconsistencies are acceptable. This is the default behavior of most distributed databases and what we are implicitly choosing when we prioritize availability.